UPDATED August 8, 2023

You’ve likely heard the sales pitch before:

- there will be fossil CO2 emissions we simply cannot eliminate

- even once we do reach actual or near-zero fossil CO2 emissions, we’ll need to “draw down” CO2 from the atmosphere to avoid the need to cope with global warming long-term

- renewable energy will be super-abundant and super-cheap one day, so designs predicated on the notion of wasting vast quantities of it aren’t as stupid as they might seem on their face

- yeah, I know, that last point wasn’t convincing, and it really is stupid right now, but we need to work on it so it’s ready when we need it

What am I talking about? Direct air capture- the act of using active mechanical/chemical equipment and vast quantities of renewable energy, in a totally pointless fight against entropy, to try to suck CO2 out of the atmosphere for either durable burial or “use”.

You’ve all seen the images- CGIs of vast rows of giant vacuum cleaners, fixing the problems of history. Hurray! The deus ex machina solution to climate change has arrived. Go on sinning, folks- keep burning fossils with wanton abandon! Because some day, some bright propellor-heads will find a way to just suck our sins back out of the atmosphere!

Do you see the danger of that fantasy? I certainly do. And as a chemical engineer, I realize how preposterous it is to even think about moving minimum 1600 tonnes of air around mechanically to have the hope of removing 1 tonne of CO2 from it at 416 ppm.

DAC: The Idiot Cousin of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS)

Let’s be crystal clear here: you’ve likely heard people say things like “CCS doesn’t work”. They’re wrong. CCS works just fine in terms of its real objectives, which are captured in this, the most accurate and concise reference in relation to CCS that I’ve yet come across:

(Warning- language might make a sailor blush!)

Yes CCS works just fine, in terms of extending social license for fossil fuel use, and as a marketing tool for the fossil fuel industry, and in terms of regulatory capture etc.

Update: don’t take my word for it- take the fossil industry’s word for it!

“We believe that our direct capture technology is going to be the technology that helps to preserve our industry over time,” Occidental CEO Vicki Hollub told an audience at CERAWeek, an oil and gas conference, earlier this month. “This gives our industry a licence to continue to operate for the 60, 70, 80 years that I think it’s going to be very much needed.”

Even if you are to look at it technically, CCS works just fine- you just can’t afford it, even under nearly ideal conditions.

This video does a good job of taking the mickey out of the whole “clean coal” thing, which was predicated on CCS “working”. It’s worth a watch, and is a good laugh- though not quite as good as the Juice Media one above:

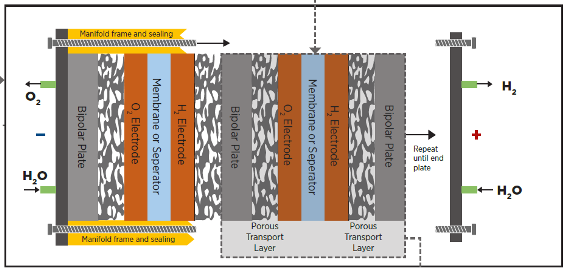

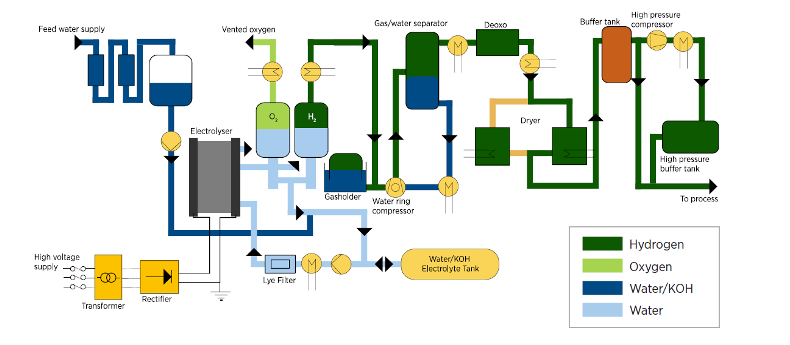

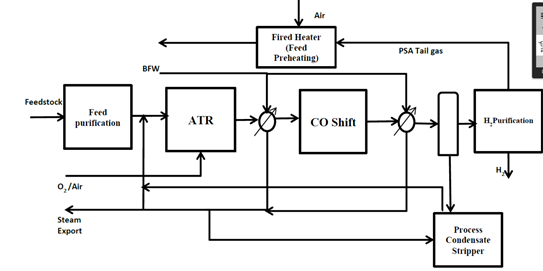

How do I know that CCS works “just fine”? Because the “capture” part is done routinely by the fossil fuel industry day in, day out, as a normal part of business. Every hydrogen generation unit on earth does it. Every liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant does it. Most of the fossil gas processing plants do it too, removing some CO2 to get the gas up to pipeline spec in terms of energy content. And a great many chemical plants remove CO2 from either feedstocks or product streams, because the gas gets in the way otherwise.

In chemical engineering terms, the capture part is childsplay, because CO2, aside from being bigger and bulkier, also has a “handle” on it that other gases in the atmosphere like N2 and O2, and the methane that makes up most of fossil gas, don’t have. CO2 is an acid gas, and so it chemically reacts with bases. And that reaction can be made reversible, too. So we can use that “handle” to separate it out selectively from mixtures of other gases.

Of course if the atmosphere can be treated as a free or very cheap public sewer, you don’t bother with the “S” part- you simply vent the gas once you’ve collected it. And if that alternative is on the table, there’s no big impetus to put a whole lot of effort and energy into making sure your “CCS” project meets its design objectives- so, sometimes these projects don’t. And often, it’s for reasons other than the “capture” part. Gorgon, for instance, is having trouble with the “storage” part, because the reservoir they want to dump the CO2 into, needs to have water pumped out of it- and the receiving reservoir for that water is clogging up with sand. Or something like that- anyway. Ask a geologist.

The Basics of CCS

Any time you try to take a dilute mixture and make it into a concentrated mixture, you’re going in the opposite direction to the one the 2nd law of thermodynamics says that things go spontaneously. The spontaneous direction is for concentrated things to become dilute, hot things to become cold etc. etc. By trying to go in the other direction, you’re locally decreasing entropy, by pushing something up a concentration gradient. No problem, says the 2nd law- you simply have to pay your tithe in terms of energy, and ensure that the entropy of the entire universe increases in net terms when you’re done. The bigger the concentration gradient, the greater the entropic “tithe”- the more energy you need to use to make it happen.

It stands to reason. Imagine you’re given 100 golf balls- all white, except one. You can look at each ball, but only one at a time, and you can’t stop looking when you’ve found the orange one- once you’re in, you’re committed to looking at all 100. Wow, what a pain! But you could do it, if for some reason you really wanted that one orange ball.

Now let’s say that instead of 100, it was 10,000 balls, and still only one orange one…

You can see that the lower the concentration, the more of a pain in the @ss this is going to be. That’s the 2nd law.

In terms of gas mixtures, the thing that really matters is the partial pressure. The partial pressure is the product of the volumetric concentration of the gas, and the total pressure.

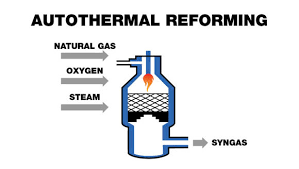

Take, for instance, the syngas stream coming out of a steam methane reformer. The gas mixture is about 15-20 volume % CO2, at a pressure of about 25 bar(g). The partial pressure of CO2 is therefore about 0.15*26 =~ 3.8 bar.

Let’s compare that to the atmosphere. It’s 416 ppm CO2 at a total pressure of 1 bar(a). That’s a partial pressure of 0.000416 bar.

Hmm- looks like getting the CO2 out of the 1st one is going to be quite a bit easier than the 2nd one, eh? Yup. Way, way easier. You need to process 3.8/0.000416 or around 9100 times as much gas volume in the case of the atmosphere, to obtain a tonne of CO2- assuming that you captured it all.

But in fact the partial pressure we’re most concerned about is the partial pressure at the discharge, not the inlet. So doing 90% capture (removing all but 10% of the CO2 in the incoming gas stream) takes considerably more energy than doing 50% capture- not just because you have to process more gas, but you have to do a better job of “sifting” it.

There are other complexities, but to a first approximation, the following are borne out when you look at CCS projects in the world:

1) The stuff you’re removing the CO2 from, has to be worth money, and the CO2 must be a problem, otherwise you won’t bother removing it.

2) The partial pressure of the CO2 has to be pretty high to make it worth the bother of removing it.

3) That means either the concentration of CO2, the total pressure, or preferably both, need to be high, or you won’t bother doing it

4) That means process streams, rather than waste gas streams, are the main thing you’re going to remove CO2 from, because they’re easy, i.e. they require less expensive energy

5) Combustion equipment usually doesn’t operate at high pressure, and is usually carried out using air (which is 79% useless nitrogen), resulting in low CO2 partial pressures- so post-combustion CO2 capture is unusual (though it is done- when the desired product is CO2, for instance for carbonating drinks)

When you look at “CCS” projects therefore, what you usually find are projects like Sleipner and Gorgon, where there’s a lot of CO2 in an otherwise valuable fossil gas stream coming up from the ground under pressure, which must have its CO2 removed before it can be monetized, and where the CO2 is being buried rather than vented for regulatory reasons (i.e. venting isn’t allowed by the local government).

Rarer are projects like Quest, the blackish-blue bruise-coloured hydrogen project in Alberta which is burying 1 million tonnes of CO2 per year which must be removed from the hydrogen, but which ordinarily would be vented- except instead, the Canadian public through their tax dollars are paying to bury it instead.

What you rarely see are post-combustion CCS projects, where CO2 produced from energy production such as burning fossil gas or coal is captured and then buried. Why not? Low partial pressure, meaning high energy cost, and extra cost due to loss/destruction of the bases (amines) used in the carbon capture equipment. In those cases where post-combustion CO2 capture is carried out, invariably the proponents seek to monetize the CO2 by doing enhanced oil recovery. And that, folks, really isn’t CCS- it’s a way to “dryclean” an existing oil reservoir to recover more oil, and only a fraction of the CO2 injected remains buried. EOR is an attempt by the fossil fuel industry to be paid twice for its CO2- and while post combustion CCS is better than mining naturally occurring CO2 for this purpose, the even better choice is to stop mining fossils for the purpose of burning them.

Forget About CO2 Re-Use

And please, for once and for all, let’s forget about the “use” thing, i.e. CCUS. Let’s be clear about what CO2 is: it’s a waste material. The very thing that makes CO2 (and water) a valuable product of energy producing reactions like combustion, makes it a poor starting material from which to make much of anything useful. What is that thing? Low Gibbs free energy, i.e. low chemical potential energy. Think of fuels as sitting on top of a chemical potential energy cliff. Throw them down the cliff by reacting them with oxygen to make products like CO2 and water, and you liberate chemical energy. But the 1st law of thermodynamics says that you must put back all that energy if you want to start with CO2 and water and use them to make fuels again- and the 2nd law says that each energy conversion is going to come with losses. As it turns out, the losses involved in climbing that particular cliff are very, very steep indeed.

Of course some readers are scratching their heads or perhaps throwing chicken bones at their computer screens right now, yelling that CO2 (and water) is the basic building block of life on earth. And yeah, you’re right. Plant life takes CO2, water and the energy from sh*tloads of visible light photons, collected and stacked up on top of one another in an incredibly complex chemical shuttling process called “photosynthesis”, to produce carbohydrates- the stuff from which plants are made and the stuff (nearly) the entire rest of the ecosystem uses as a source of chemical energy (i.e food).

Nature’s been at this for about a billion years, and has managed some shocking leaps forward in the efficiency of photosynthesis. The energy efficiency, after all that time, is about 2% at best.

Why? Because it’s frigging hard to do. Nature does this because a) the sun is a limitless source of energy b) to nature, time is irrelevant and c) it has no choice.

There are a handful of highly oxygenated chemicals which might be worth making from CO2, water and electricity in the future. The only one of them which is a “fuel” in meaningful terms, is methanol- and right now, all the methanol in the world is made from fossil gas via the manufacture of syngas, without CO2 capture. Fortunately, most of the methanol produced in the world is like almost all the hydrogen- it isn’t wasted as a fuel, but rather is used as a chemical.

Reference Costs

Shell Quest provides a great reference. The article I wrote about Quest, linked above, provides links to the public sources of information about the project. It was done by experts, not dummies- it was designed and executed by Shell and the giant EPC Fluor. Conditions are ideal- high partial pressure CO2 in process syngas is all they go after, capture percentage target is modest (80% of the CO2 in the syngas), and they have an ideal hole in the ground to stuff the resulting CO2 into, only 60-ish km away.

What does it cost? $145 CDN per tonne of CO2 emissions avoided. Shell claims on the project website that they could do the next project “for 30% less”, but that was before COVID/wartime inflation. And in facilities terms, net of the energy (heat and electricity) used to run the CCS equipment, capture is terrible- only 35% of the CO2 in net terms is captured. Figure in the methane emissions and CO2e capture is even worse- by my estimates, only about 21%.

Too expensive. By the time a reasonable payback on capital, realistic costs of energy and some profit are included, the cost of doing this is north of what carbon taxes will be in Canada even in 2030- even assuming we keep electing pro carbon tax governments (and I sincerely hope we do!). Unless carbon tax levels are both high and very certain, nobody is going to do this without additional government “help”. That means taking money collected in taxes on things we want, or should want, i.e. people and businesses making goods and services of real value- and using those funds to pay the likes of Shell to bury its effluent.

So much better to just reduce how much effluent we generate, by buying less of Shell’s products!

Why does DAC Suck?

As you might have concluded from the foregoing, DAC sucks not just because of its obvious use as an insincere strategy to keep us burning fossils for longer based on a false hope- but also because the partial pressure of CO2 in the atmosphere, though higher than we can tolerate in climactic terms, is very low indeed in absolute terms: only 0.000416 bar. That means you’re involved in not only an entropic fight, requiring lots of energy to capture even a little CO2, but you also generally have to move a lot of air around mechanically to make it work out. And there’s a lot of other stuff in air- dust and dirt, water vapour and the like- which can screw up your equipment, depending on how you do it.

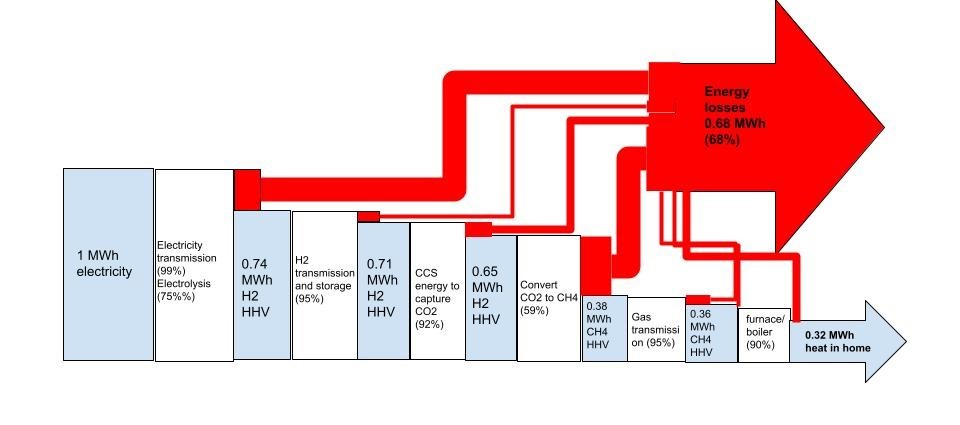

As badly as “blackish blue” hydrogen looks, doing that would be much smarter than doing DAC. And capturing the CO2 from calciners making cement from carbonate rocks, would make even more sense- especially if those calciners were electrified using renewable electricity.

The energy use inherent to the thermodynamic foolhardiness of DAC means that DAC is, until we stop burning fossils as a source of energy, basically an energy-destroying Rube Goldberg apparatus to rival something out of an OK Go video:

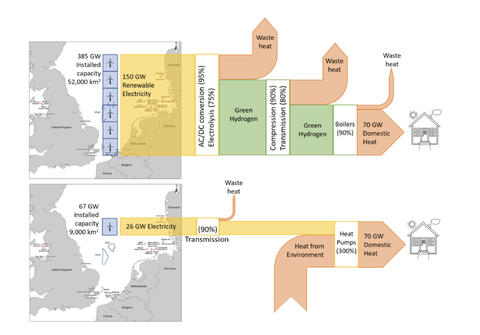

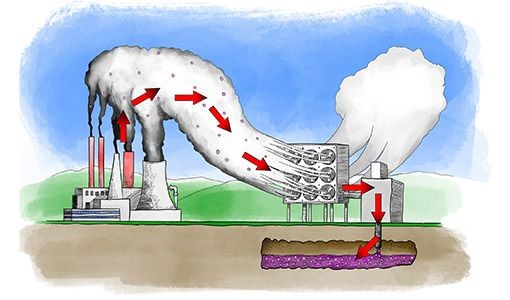

Here’s a hilarious bit of inadvertent accuracy on the part of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in relation to DAC- an image which is missing only the wire connecting the polluting power plant to the useless DAC machine!

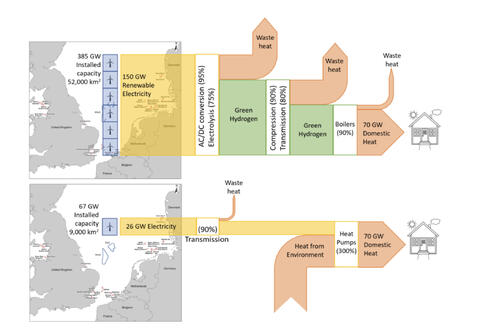

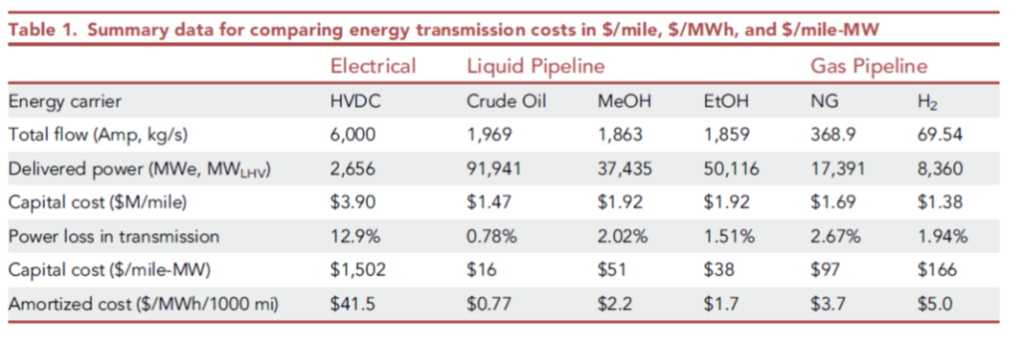

As I’ve said many times: over here, on the left hand side of the image (most of the world sadly!) we’re burning fossils to make energy. Over there, on the right hand side of the image, we apparently have vast amounts of renewable energy which we want to waste by running an energy-destroying Rube Goldberg apparatus. The obvious solution is to connect “here” and “there” with a WIRE, and throw away the worthless, energy-sapping molecular middleman!

DAC’s Biggest Players

There are plenty of players trying to suck up the credulous, foolish funding for DAC approaches being offered both privately and through government agencies, but the two main proponents at present are the (regrettably) Canadian company Carbon Engineering, and the Swiss firm Climeworks (whose image I modified for this article). There are also “passive” DAC approaches, such as people trying to grind up silicate rocks so they can “weather” and become carbonate rocks quicker than they would naturally. Those approaches have their own problems, but they’re not the target of this particular missive on my part- you’ll need to wait for a future article for me to take them on. In this one, my sights are set firmly on the big, iconic, CGI-generated vacuum cleaners- my target is the “meme” of DAC.

Carbon Engineering’s approach is to use a two step process. A strong base (potassium hydroxide) is used to capture the CO2 in the big vacuum cleaner thingies, making their DAC equipment quite a bit smaller and more practical than if a weaker base were used- but at the cost of making regeneration of that base, harder and more energy-intensive (thermodynamics sucks, doesn’t it?). Their solution is to use the calcium oxide cycle, generating calcium carbonate as their strong base is recycled. The calcium oxide is regenerated from the calcium carbonate- get this- by burning fossil gas…

Their principal investors, Chevron and Oxy Petroleum, are interested in using DAC to produce CO2 for use in EOR, while also harvesting credulous government money for CCS credits. Wonderful! Michael Barnard has done a marvelous job of bashing this dumb scheme already, so I don’t need to bother doing any more than pointing you to his excellent work. He calls Carbon Engineering “Chevron’s Fig Leaf”, and I cannot disagree.

The other guys, ClimeWorks, use a “highly selective filter material”- what this is, is not clear, but it appears to be a base fixed to a solid. The base is then heated to 100 C to drive off the CO2. No, they get no entropic benefit from any magic beans in their “filter”- they’re fighting the same pointless battle that Carbon Engineering and the rest are fighting, just using different tools. But at least ClimeWorks doesn’t burn fossil gas to regenerate their “filter”- they power their units with “100% renewable energy or waste heat”. Their big showcase project is in Iceland, where clean-ish geothermal electricity and heat is used to run their DAC machine. The resulting CO2 is injected into water returning to a volcanic aquifer rich in silicates. Over a period of years, the CO2 in this water “weathers” the silicates, converting them to carbonates.

ClimeWorks seems to have settled on the business model of voluntary carbon credit harvesting. Pay us to capture and bury your CO2, at the low low price of $1,100 USD per tonne!

Wow- imagine the real emissions reductions we could do for way, way less than $1100/tonne…Like electric vehicles, where the car costs more, but the total cost of ownership to the vehicle owner- and hence the cost per tonne of CO2 emissions abated- are in fact negative to the vehicle owner…

But hey, I get it. The big vacuum cleaners to the rescue will let some people drive their big, dumb pickup trucks with a little less guilt- even if those DAC units are just proposed and not actually built…

Carbon Negative Technologies Which Work

I can hear the complainers already. “You just sh*t on everything everybody else is doing- what are your solutions?”

I’ve laid out my solutions very clearly. I’ve even mis numbered them, so your solution can be slotted in where you see fit:

What are the solutions? Read the $)(*@#$ article! But in summary:

1) Make CO2 emissions cost something- a high and durable price

2) Stop wasting precious, finite fossil resources as fuels. Use them instead to make the 10s of thousands of molecules and materials every bit as essential to modern life as is energy, but which are far, far harder to make starting with biomass much less CO2 and water and electricity! Electrify everything instead. And if you think you can’t electrify it, try harder.

3) We’ll need some liquid fuels in the future, for applications like long distance aviation which simply cannot do without. Don’t make them the lugubrious way using CO2, water and electricity, because that’s nuts. Instead, start with biomass. Yes, the cheapest way is using food biomass, because all of agriculture so far in human history has been optimized around getting plants to put as much energy into the parts we harvest for food as possible. But we can also start with cellulosic materials- wood waste, corn stover, sugarcane bagasse, rice and wheat straw etc. Make those fuels via pyrolysis, produce biochar and return that to the fields and forests the source biomass came from, closing the inorganic nutrients loop and providing a service formerly provided to the ecosystem via wild fire- something humans simply cannot tolerate. Yes, the resulting fuels will cost a fortune, but they’ll be cheaper than e-fuels, and every mile flown by rich people on jets will have the net result of taking carbon OUT of the atmosphere and tying it up for centuries if not millenia in the soils. But don’t expect that to happen voluntarily- you’ll need to force it via regulation or it just will not happen. I like this char approach much better than other bioenergy plus carbon capture and storage schemes (BECCS). Burning wood and doing post-combustion CCS is pretty much a non-starter based on my analysis, though some like Drax in the UK are betting big on it.

Disclaimer

This article was written, pro bono as a public service, by a human who was sipping home-made cider and writing about something he thinks is important, on a Friday evening, instead of watching Netflix. That human has no money riding on any of this one way or another- he has no EV company stock, nor is he shorting Carbon Engineering etc. But because a human was involved in the writing, there is some emotion in there, as well as the possibility of error. Show me where I’ve gone wrong, with references, and I will gratefully edit the piece to reflect my more fulsome knowledge.